EU to not release assessment of Pakistan General Elections 2024

EU will not release its expert assessment of Pakistan General Elections 2024 as it will undermine relationship with the Government.

This section is a collection of half baked academic ideas burrowed or original, but not fully developed. Many posts are my attempts to get published elsewhere.

EU will not release its expert assessment of Pakistan General Elections 2024 as it will undermine relationship with the Government.

Since February 8th, 2024, X, formerly known as Twitter, has faced severe disruptions in Pakistan. Researchers are keen to understand

Since the acquisition of X, formerly Twitter in 2022, by Billionaire Elon Musk, serious allegations of hateful and conspiratorial content

Despite predictions to the contrary, PTI’s ability to mobilize support has disrupted conventional wisdom, impacting Pakistani democracy.

Based on his experience & analysis about the novel coronavirus so far, Najam sb speaks on the magnitude of disruption

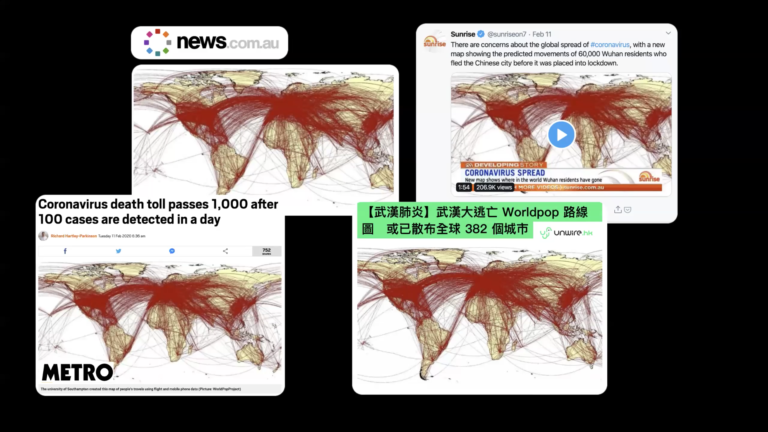

Discussion on misinformation about coronavirus with three experts organised at Hong Kong Baptist University.

A religiously fuelled violent protest that brought the nation to a standstill has subsided. For now. Once again ordinary Pakistanis

Most of us have travelled by road to Northern Areas alongside the twists and turns that characterise the spectacular banks

Recently scholars at the opening meeting of the premier International Communication Association conference, cautioned against the role of ‘fake news’ in

But going beyond the human rights perspectives on a restricted public sphere commonly associated with closed societies, question remains whether a more connected Pakistan will be conducive to deliberative and representative discussions en masse to begin with.