There is an on going debate in Pakistan echoing global concern about the extent to which social media is simply replicating moribund and traditional impulses of the society.

The debate

The young ones are optimistic. With some reason. Just take a sample of the rich tapestry of awareness and advocacy currently on social media; a campaign to push for peace between India and Pakistan on Change.org initiated by folks on both sides of the hostile border; a funny viral video by fans of an opposition party around the recent ouster of the Prime Minister on corruption charges; accusation of stifling a story on injuries from an incident during a TV program shot in Pakistan’s premier gated community by a popular blogger, an online furore over a television anchor who had verbally abused a female guest on ‘patriotism’ during a live transmission.

More senior journalists and informed observers are cautious at best. A report by Bytes for all, a local Internet advocacy group, last year highlighted the increase in arbitrary government blocks on websites. While this year marked the first reports in the press on state-suspected attacks on online activists.

But going beyond the human rights perspectives on a restricted public sphere commonly associated with closed societies, question remains whether a more connected Pakistan will be conducive to deliberative and representative discussions en masse to begin with.

I want to bring attention to the copious amount of abuses and barbs traded by partisans on social media. Be it the progressively inclined fans of opposition parties, the conservative activists of the government or some combination of both. These ‘echo chambers’, to borrow a term from political communication, are by far the most prominent aspects of political discussions online. The notable journalist, Najam Sethi, goes as far as to refer to a thriving ‘anti-social media’. Where discussions are rich on emotions and rhetoric, little on substance and reminiscent of crazy talking heads on television.

Consider Youtube.com.pk, an open online public space, in a similar vein, setting aside for a moment the government’s absolute authority to ban it. Even a cursory look at the weekly trending will reveal mostly sensational television news stories regurgitated online, South Asian television soaps and films, ‘item numbers’ (bawdy dances of women on a background of Indian songs) and a sprinkling of Islamic evangelical content.

It appears that the roughly 28 million strong Internet user base, which by the way is no trivial figure (the entire population of Hong Kong is roughly 7 million), of highly educated Pakistanis, according to a recent survey on her Internet User’s Perspectives, seem mostly concerned with entertainment values in all their variants we usually associate with the ‘old’ broadcast age.

And while there is hardly any research on the quality of discussions Sethi isn’t far off the mark either. They fit our understanding of authoritarian emerging media conditions where most online content is used for broadcast purposes, traditional media successfully co-opts online spaces and a civil society voice is further confined or lost in the cacophony of misinformation.

Evegny Morozov in his cynical, albeit astute analysis, cautioned against cyber-utopianism; “a naïve belief in the emancipatory nature of online communication that rests on a stubborn refusal to acknowledge its downside”; that instead of serving as a panacea in the market place of ideas there is a growing fear that Internet in Pakistan is becoming a game changer for established individuals, politicians, television personalities and (retired) generals who now find it even more convenient to build on their offline persona.

Social media and political parties

How far has Pakistan’s emerging online culture succumbed to Morozov’s worst fears? My on going research aims to answer this question partly by examining the logic of her social media for civic engagement.

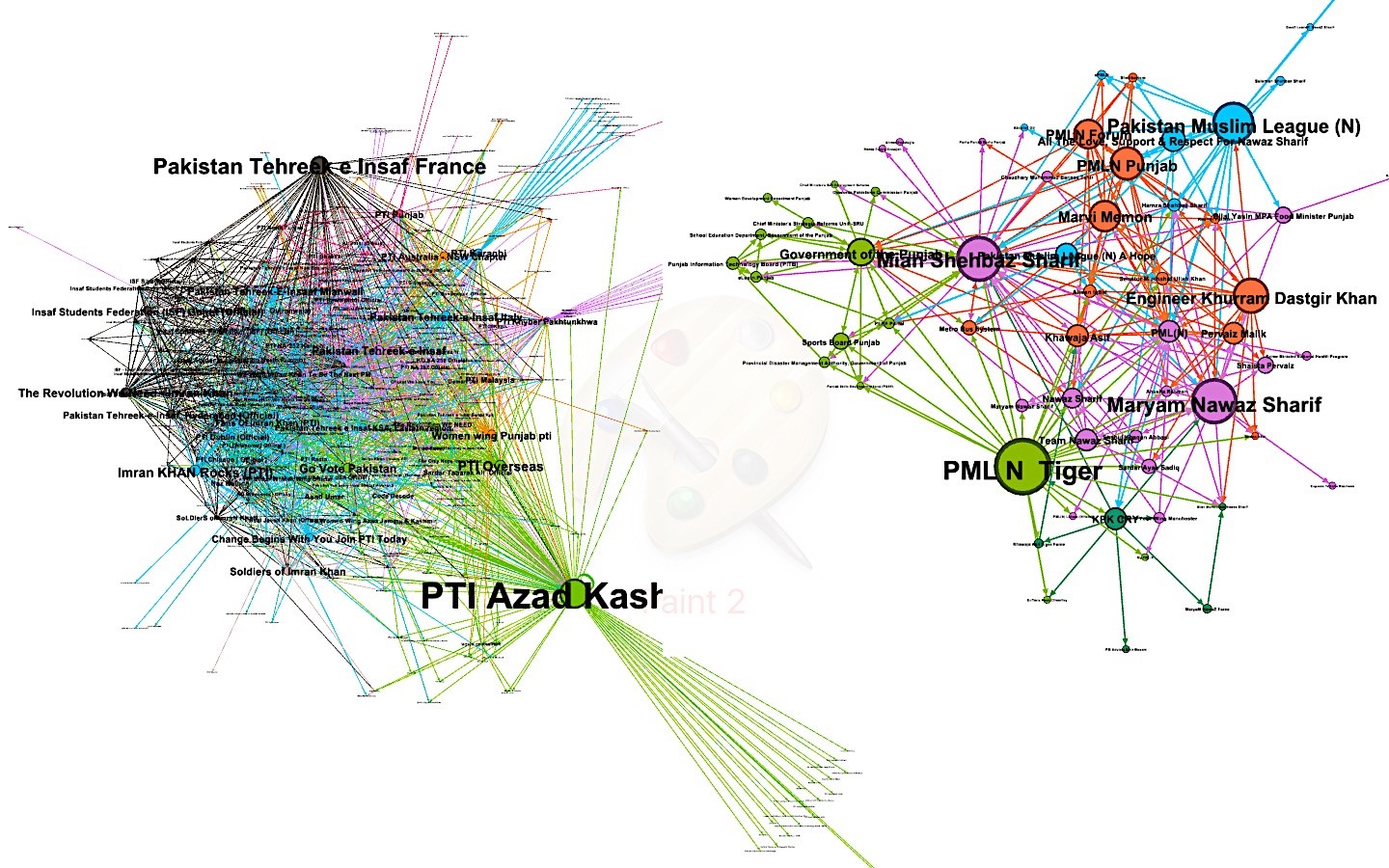

Figures 1 shows a social network analysis (SNA) I conducted based on the Facebook Page ‘like’ networks for two major political parties – the Pakistan Muslim League Noon (PMLN) in the government, and its nemesis the Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf (PTI) in the opposition. SNA uses mathematical tools to understand the relationship (‘like’) between nodes (Pages) and the overall structure (Network) they are embedded in. It is often used to understand online organisation. The analysis reveals that the PTI has five times the online presence, 319 Pages, of PMLN, 66 Pages. Although offline, the latter commands a much larger share in the National Assembly. In fact the situation is reversed; PMLN has roughly five times the seats of PTI!

|

| Figure 1. PTI Facebook ‘like’ network (left) & its PMLN counterpart (right). The size of labels represents level of activity of pages. Thus overseas pages are most active on PTI network. Similar colours reveal pages that depict similar patterns of connectivity or community. For PTI; green = Azad Kashmir related, Black = Insaf Student & fans related, Purple = KPK related, Blue = Karachi related. The much smaller PMLN has been disproportionately enlarged for clarity’s sake. No clear communities are visible likely due to network mostly formed by techy savvy politicians as opposed to activist teams. Note: SNA visualised on Gephi using publicly available Facebook data. The latter is the most used social media platform in the country. |

This shows the considerable disconnect between on-ground (offline) and online reality and could be of some consolation; notwithstanding the limited importance of online campaigning in Pakistan the gap means that there is some way to go before the ills of patronage and dynastic politics completely colonize online. An uncertain window that the marginalized exploit and the youth are optimistic about.

But for many it is primarily the digital divide that has limited marginalized voices to the fringe of public opinion proper. As if more Internet is just what is required to keep the window open or for more people to support progressive causes. Pick any recent report mapping media trends in Pakistan and you find a similar introduction emphasizing the poor state of Internet development.

The PTI case is illuminating here as well; its largest constituency lies in Khyber Pakthunkhawa (KPK). Those familiar with South Asian geography will recognize this rugged province, that shares a border with Afghanistan, as having very low Internet penetration compared to the rest of Pakistan. Clearly there are factors beyond simple voting considerations that seem to inform the party’s online strategy; reviving overseas Pakistanis, creating awareness among urban youth, supporting advocacy causes (see figure 1) and raising funds.

It’s complicated

Similarly, the digital divide is but one factor, and not necessarily the most important one, Pakistani policy makers should bank on if they are serious about diversity in the online market place of ideas. Media literacy; critical thinking; the capacity of journalist and bloggers for investigative work, contribute equally, if not more, in this equation. It will be an uphill battle. These concerns require novel solutions that go beyond simply paving and clearing information highways.