I participated in a panel on ‘journalism practice in a post-truth era’ at Karachi University

I participated in a panel on journalism practice in a post-truth era at Karachi University.

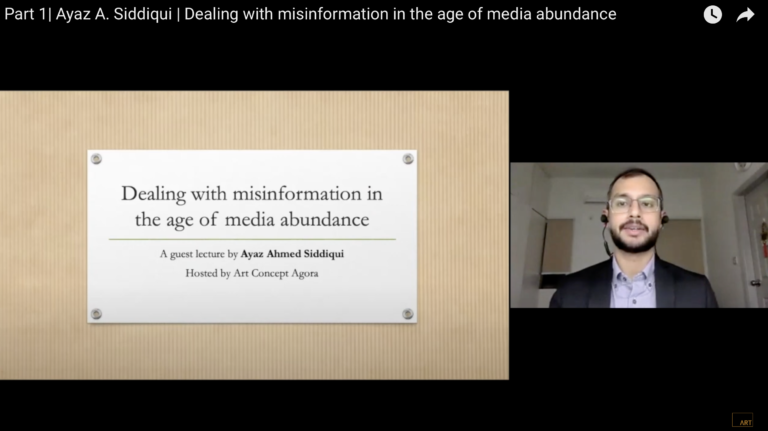

This section is a collection of my published material such as opinion pieces, conference presentations, articles, posters and even essays for admission purpose.

I participated in a panel on journalism practice in a post-truth era at Karachi University.

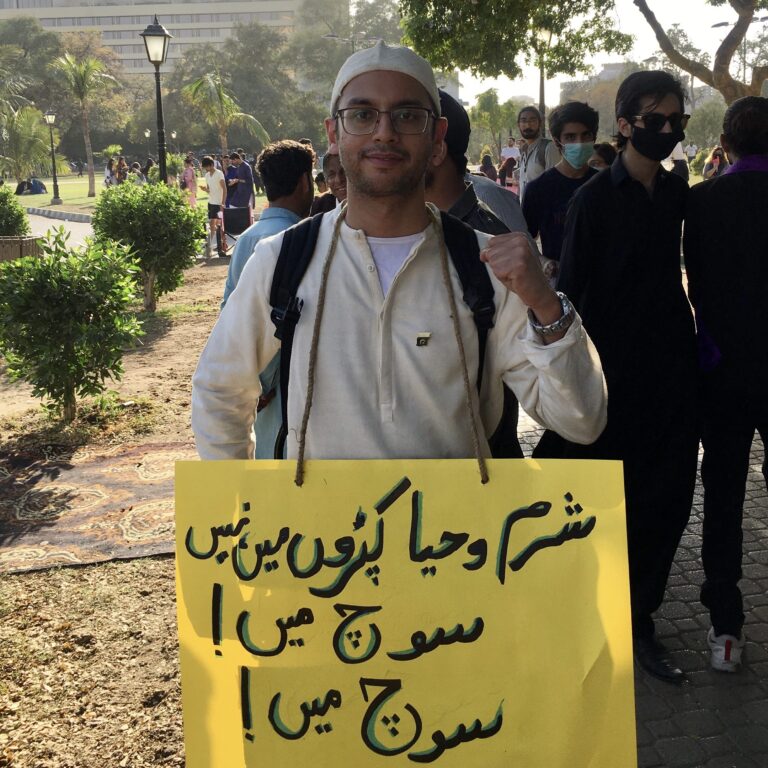

How can a few posters raised once a year in major urban centres by a tiny group of hapless womxn volunteers shake the militarised Islamic Republic of Pakistan? Answer: media power

When is media content functional and dysfunctional?

In my latest essay for the Interface: a journal for and about social movements, I explain how the artistic expression

Learn more about the Aurat March 2020 through the eyes of a researcher on social movements in Pakistan.

Leaders must convince – not coerce or fool – people in to following state policies, such as high taxes. For this they must speak the truth. Good intentions are not enough

Originally published in theWire.in. The first time I set foot outside Pakistan was on a trip to Turkey to meet

Typically it is assumed that the rote learning centric public education system is the root of our jahalat (‘iliteracy’ – if transliterated from Urdu; ‘incivility’ – more accurately as I will now argue).

Doing journalism where public life is synonymous with violence Originally published in Media Asia. Dawn, Pakistan In Pakistan, the politics

Originally published in The News on Sunday, August 13th 2017. In their vehement critique of the media industry, Herman and